|

OAKLAND, Calif. (CN) – Attorneys for a developer fighting to reverse a ban on coal-handling in Oakland suggested in a Tuesday bench trial that city officials conspired to enact the ban to appease their environmental allies.

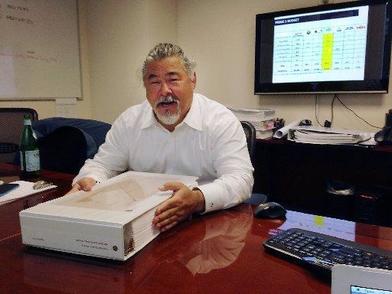

“It’s a big deal for Oakland to alienate the Sierra Club, right?” the developer’s attorney Meredith Shaw asked, referring to one of the most well-known environmental groups in the United States. “The Sierra Club can make or break politicians, right?” Developers of the Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal (OBOT) – including Phil Tagami, a friend of Gov. Jerry Brown – want to haul coal by train from nearly 1,000 miles away in Utah and ship it to Asia through the $250 million facility. The terminal is being built on an old army base in West Oakland. But in June 2016, the Oakland City Council passed two measures prohibiting the storage and handling of coal and petroleum coke at any bulk materials facility in the city after multiple studies found that coal dust blowing off trains can cause asthma or cancer. The new regulations brought the project to a halt. Tagami sued the following December, claiming the ban violates the Constitution and a 2013 development agreement between OBOT and the city. Tagami, whose Oakland-based real estate firm California Capital and Investment Group owns OBOT, says the city knew before signing the development agreement that the terminal might handle coal, then caved to political pressure from environmental groups after four Utah counties said they planned to invest $53 million in the terminal to export their coal. On Tuesday, Tagami’s attorneys tried to prove the city pressured its expert, Environmental Science Associates, to produce a report that would “support a coal ban.” According to them, the report was based on faulty math and used the wrong standard for estimating the amount of emissions the terminal would create. This led to the conclusion that the terminal would create six tons of emissions a year, 17 times more than it actually would, the attorneys said. Environmental Science Associates’ Victoria Evans, the report’s project manager, testified that Oakland rejected her firm’s proposal to model the air quality issues the terminal would create, instead directing it to submit a review based on “limited information.” She also said the Bay Area Air Quality Management District – the regional agency charged with protecting air quality – told the environmental planning firm that its permitting requirements would reduce terminal emissions by 95 percent. But Evans denied the city told her team to produce a report justifying a ban. She said the report didn’t consider placing covers on rail cars carrying coal or spraying down the coal with a chemical surfactant before a train trip – two measures OBOT proposed to stop coal dust from blowing off trains into West Oakland – because no scientific data shows that either solution works. Surfactant cracks after 100 miles and allows coal dust to escape, and putting covers on rail cars can cause coal to catch on fire, she added. “The whole concern is coal outgasses methane, and methane is combustible. With coal dust around as well, there is the opportunity to have smoldering coal piles, and bad things happen,” Evans said. Tagami, who also testified Tuesday, said the terminal would temporarily shut down if it exceeded pollution standards set by the city and the air district, rendering a coal ban unnecessary. But on cross-examination, he acknowledged that coal sitting idle on trains and in conveyors while the terminal gets back into compliance could also catch on fire. Oakland says it has the right under its development agreement with OBOT to enact health and safety regulations like a coal ban when “substantial evidence of a substantial danger” to public health exists. It says it doesn’t want to exacerbate pollution in West Oakland, a community primarily composed of poor people of color that already suffers from some of the worst air quality in California due to its proximity to major freeways and the Port of Oakland. West Oakland residents die 12.4 years sooner than residents in richer Oakland neighborhoods, and the estimated lifetime potential cancer risk in West Oakland from emissions from the port is about seven times that of the region as a whole, according to an amicus brief filed by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra. At a Jan. 10 hearing on the parties’ opposing motions for summary judgment U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria suggested he may allow the city to gather additional evidence to satisfy the substantial-evidence standard if he finds it didn’t do so the first time. OBOT’s lawyers balked. But Chhabria seemed to support the move again on Tuesday when he asked Evans whether her report would allow him to compare OBOT’s emissions with those of similar facilities, and whether such comparisons could be made if they weren’t already. She said some comparisons could be made. Evans will testify about the terminal’s health impacts on Wednesday. The trial concludes Friday. Shaw is with Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan in San Francisco. Gregory Aker with Burke, Williams & Sorensen in Oakland argued for the city. https://www.courthousenews.com/city-accused-of-bowing-to-political-pressure-in-coal-ban-trial/

1 Comment

Oakland coal lawsuit turns into money train for outside lawyersThe cost of keeping coal out of Oakland is burning through the city’s bank account. City Attorney Barbara Parker has spent nearly $1.4 million for outside attorneys to defend the city in a breach-of-contract lawsuit brought by developer Phil Tagami, who was prevented by the city from carrying out plans to move millions of tons of coal a year through a shipping terminal he wants to develop on the old Oakland Army Base. And the bills just keep on coming — the case hasn’t even gone to trial yet. Records provided by Parker’s office show that payments have been made to four law firms, with the bulk — $1.2 million — going to Burke, Williams & Sorensen. Its lead attorney, Kevin Siegel, is himself a former Oakland deputy city attorney. “When we are up against high-priced law firms spending on the other side, we can’t just use second-tier lawyers for our side,” said Councilman Dan Kalb, who is among those battling to keep coal processing out of Oakland. “Not that we are using the most expensive we can get, but they are very good lawyers and not necessarily cheap.” The fight dates back to 2013, when Tagami — a friend of and longtime fundraiser for Gov. Jerry Brown, a former Oakland mayor — won the city’s blessing to build a $250 million bulk cargo terminal on the old Army base. Despite his assurances that he had no plans to handle coal, Tagami secured a deal in 2015 to move up to 10 million tons of it annually through the terminal. The coal would be shipped by rail from Utah, loaded onto ships and sent off to Asia, making Oakland the top coal exporter on the West Coast. That brought howls from City Hall and environmental and social justice groups opposed both to Oakland having anything to do with coal, a big source of greenhouse gas emissions, and to the parade of coal trains that would add to air pollution in West Oakland. “It’s sad he has gone against his word,” Kalb said. “He told me in 2013 that climate change was the primary issue of the day, and he would never let coal come through his facility.” Tagami refused to back down, saying the agreement he struck with the city did not include a prohibition on coal. So the City Council voted in July 2016 to outlaw any coal handling or storage within city limits. Tagami sued, claiming breach of contract and city interference with interstate commerce. Besides Burke, Williams & Sorensen, Oakland has retained the law firms Holland & Knight ($110,760); Kaplan Kirsch & Rockwell ($46,496); and Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger ($5,730). We’ll see how they’re doing starting Tuesday, when the trial is scheduled to begin in federal court in San Francisco. Oakland, terminal building go to court Tuesday over city’s coal ban  Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle - Cranes are docked near the site of a proposed coal storage and shipping facility at the Port of Oakland on Saturday, Jan. 13, 2018. Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle - Cranes are docked near the site of a proposed coal storage and shipping facility at the Port of Oakland on Saturday, Jan. 13, 2018. The company that wants to transport coal by rail to the Port of Oakland for overseas shipment says the city’s ban on coal-handling violates the Constitution, federal law and common sense. The city says it agreed to let the company build a $250 million shipping terminal after the firm’s officials falsely denied the sight would be used for coal storage and shipments. Most Popular The two sides also disagree on greenhouse gases and pollution controls. But the trial that begins Tuesday in federal court in San Francisco will most likely come down to a single question: whether Oakland, when it outlawed coal-handling and storage within its borders in July 2016, had reasons to conclude that the substance was a health hazard. Oakland's coal fight

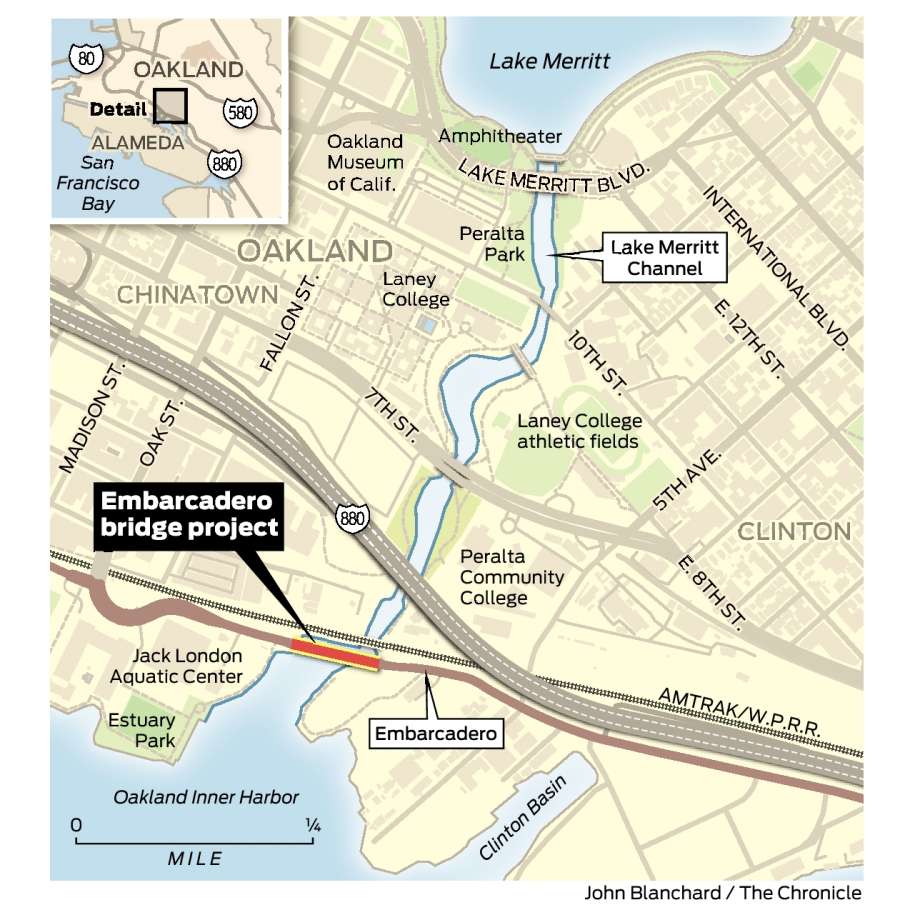

“The City Council has to have substantial evidence that there’s a substantial danger,” U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria, who will conduct the nonjury trial, said at a pretrial hearing last week. Oakland doesn’t need airtight proof, just enough evidence of potential health risks to support its ban, Chhabria told a lawyer for Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, the shipping company known as OBOT and controlled by developer Phil Tagami. But the judge also told the city’s lawyer, “You have to show a substantial danger.” The city says the primary danger comes from coal-dust emissions in a low-income neighborhood already suffering from air pollution and high rates of illnesses such as asthma. The company says it can minimize emissions with rail-car covers and other safety measures, and also contests the city’s warnings of potentially disastrous explosions and fires. Tagami is a longtime friend of Gov. Jerry Brown and owns the seven-story building near Oakland City Hall where Brown and his wife, Anne Gust Brown, were married in 2005. As mayor of Oakland, Brown appointed Tagami to positions on the Oakland Port Commission and, as governor, appointed him to the state medical board. But the governor has also praised the city’s 2016 ordinance and said California should “eliminate the shipment of coal” through its ports. Tagami’s project would move coal from Utah by rail to the terminal his company would build on city-owned land in West Oakland, at the site of a former Army base, and from there to ships for export. In a court filing, city lawyers said Tagami had secretly discussed coal with potential partners on the project since 2011, but told city officials in 2013, shortly after signing the terminal contract, that his company had “no interest or involvement in the pursuit of coal-related operations.” As late as September 2015, the city said, the company’s formal design plan said the facility would handle “Commodity A,” which later turned out to be coal. But the company says it was Oakland that acted deceptively in passing the 2016 ordinance. The City Council showed its hand in June 2014 by unanimously adopting a resolution opposing coal shipments through Oakland, lawyers for OBOT said in court filings. As council members posted “No Coal in Oakland” signs on social media, and Mayor Libby Schaaf told Tagami in a May 2015 letter that “we will not have coal shipped through our city,” the council commissioned dubious studies to support its preordained decision to ban the shipments, the lawyers said. The city ignored evidence of the safe handling of coal at terminals in Long Beach and Pittsburg, and brushed off recommendations by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District to prevent coal-dust emissions by putting protective covers on rail cars, OBOT lawyers said. “If the covers don’t work, we get shut down” and won’t object, company lawyer Robert Feldman told Chhabria at the pretrial hearing, arguing that the district’s clean-air standards would protect the public without the need for a ban. But city lawyers said Oakland can’t rely on OBOT’s safety promises or assume that the air district’s rules will protect a West Oakland population that the air quality district itself has described as “most vulnerable to air pollution’s health impacts.” The district has also acknowledged that residents in nearby Richmond have been harmed by emissions from a coal terminal in that city, despite clean-air rules, the city’s lawyers said. Oakland’s residents can’t afford “to allow 4 to 5 million tons of coal to be stored and handled based on mere assertions by the developer” that they will be protected, Kevin Siegel, a lawyer for the city, told Chhabria. The city also says the coal shipments, and their later use as fuel, would emit planet-warming greenhouse gases that, over the long term, pose “numerous substantial dangers to Oakland,” including heat and flooding. The company counters that any emissions from its shipments would have no measurable effect in Oakland. On another issue, OBOT contends the Oakland ordinance is an attempt to regulate rail transportation, which is under the sole authority of the federal government. The city says it is regulating only coal handling and storage. OBOT additionally contends that the coal ban unconstitutionally interferes with interstate commerce by saddling out-of-state coal producers with unjustified costs and obstacles to exports. Chhabria said Friday he would rule on that issue, “if necessary,” after the trial. The trial will focus on OBOT’s claim that Oakland breached its contract with the company by banning coal. The 2013 contract said it would be governed by the laws that were then in effect, with one key exception — the city could enforce new laws, like the 2016 coal-ban ordinance, if it determined, after public hearings, that they were needed to protect public health and safety. Chhabria said each side would have up to six hours in the trial to call witnesses and argue its case, with further proceedings tentatively scheduled for Wednesday and Friday. The Sierra Club and Baykeeper have intervened on the city’s side in the case and may participate in the trial. Bob Egelko is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @egelko A bridge in Oakland that was supposed to cost no more than $24 million could now come to well over $30 million, and the city says toxic dirt is mostly to blame. On top of the extra dollars, the project won’t be completed until December — two years later than the original target. Though some City Council members said they felt Oakland was being overcharged, they nonetheless approved the cost increases, reasoning, in part, that most of the funds are from the federal and state governments and that abandoning the contracts midway through construction would be more disastrous than pumping additional money into the work. “It’s extraordinary,” said Councilwoman Lynette Gibson McElhaney. “It’s way beyond what I consider normal deviations.” The undertaking to demolish and replace the 50-year-old Embarcadero Bridge that ran over the Lake Merritt Channel, just south of Interstate 880, is part of a years-long seismic safety retrofit program in California to upgrade some 2,000 bridges so they can withstand big earthquakes. To get it done, the city hired Flatiron as its primary contractor, along with T.Y. Lin International Group, AECOM and Biggs Cardosa Associates. The firms did not respond to requests for comment. In Oakland, the new bridge will be wider and taller than the old one, giving space for bike lanes and an underpass to connect Lake Merritt and the estuary for small boats. The project also includes better street lighting, landscaping, restrooms and rainwater treatment areas. The bridge is seen as a critical connection between the Embarcadero Cove, the massive Brooklyn Basin development, Jack London Square and Jingletown. At the outset, construction was supposed to begin in April 2015 and be done by December 2016. But workers at the site soon came across soil and groundwater contaminated with hydrocarbons — likely from old fuel leaks — plus lead and other metals, according to Sean Maher, spokesman for the city’s Public Works Department. The level of contamination was unexpected. That required the contractors to erect a special dam and containment booms to prevent the pollution from getting into the bay, Maher said. The soil then had to be tested and sorted by how hazardous it was to determine which type of landfill could safely hold it. The start of construction was delayed 15 months. A report from the city, which is disputing some of the contractors’ new payment requests, said that as of November just 40 percent of construction was done yet 65 percent of expenditures were gone. Contamination was only half the story. City officials have repeatedly referred to a permit dispute with the contractors, but have declined to provide details. The parties are now in mediation over the issue as well as disagreements over the cost increases. “We’ve been fighting with them for months about how much they’re asking, and we haven’t been accepting,” Mohamed Alaoui, a city engineer, told the City Council last month. The city is trying to figure out what went wrong with an initial environmental review, which didn’t catch the amount of toxins present.

“It can be a challenging science,” Alaoui said. “You go out in the field. You have specific locations where you take samples. You make interpolations from that. You assess risk levels from that, and then you move on. And in this case it did not work.” Councilwoman Rebecca Kaplan, who represents the whole city, worried that the city allowed the contractors to “intentionally lowball us so that they can come back around and hit us with these big change orders.” McElhaney, whose district contains half the project, called the higher costs “disturbing.” Councilman Abel Guillen, whose district encompasses the other half, said they were a “red flag.” Yet, at the urging of city administrators, the council voted to approve increases that could bring the total cost to $33 million. The California Department of Transportation, which administers the Federal Highway Administration funds, has approved its majority share of the cost increases. The city also will need to find about $1 million extra in local dollars for its portion. The money is expected to come from Measures B and BB, the Alameda County transportation sales taxes. Kimberly Veklerov is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @kveklerov https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/New-Oakland-bridge-expected-to-be-two-years-late-12495013.php Public Ethics commission investigates dec 18th 2017 special meeting of city council meeting1/12/2018

A federal judge said today it's unclear if the Oakland City Council had sufficient evidence when it determined coal would endanger the public.  Did Oakland's city council have sufficient evidence regarding harmful impacts to health and safety when it decided in 2016 to ban the storage and handling of coal in city limits? That's the question U.S. District Court Court Judge Vince Chhabria wants answered when a lawsuit seeking to overturn the city's ban on storing and handing coal goes to trial next week. The case's outcome will ultimately determine whether Oakland becomes one of the largest coal depots on the West Coast. Developer Phil Tagami is seeking permission to ship millions of tons of coal from Utah via rail. It would be stored in massive dump pits and warehouses at the foot of the Bay Bridge and conveyed onto ships bound for Asia to be burned in power plants. The city's 2016 ordinance banning coal handling and storage was designed to put an end to Tagami's plans. But Tagami then sued to overturn the city's ban. Chhabria decided at today's final pretrial hearing in the case that he simply doesn't have enough information to decide if the city's decision to ban coal was based on accurate evidence that showed a substantial threat to health and safety. "How do we know it's a substantial danger?" Chhabria asked the city's attorneys. The judge requested some kind of baseline or comparison, such as how much particulate matter is emitted from the city's freeways, or other industrial activities such as the ABI Foundry in East Oakland, which currently receives and burns coal to produce metals. Kevin Siegel, a private attorney helping represent Oakland, told Chhabria that it's unnecessary to have a baseline to compare the coal dust emissions to. Any increase in particulate matter measuring around 2.5 micrometers — tiny airborne particles that can embed deep in people's lungs and even bloodstream — is dangerous, said Colin O'Brien, an en environmental attorney whose organization, Earthjustice, is an intervenor in the lawsuit. Oakland residents, especially those in West Oakland near the proposed coal terminal site, are already exposed to large amounts of this PM 2.5 dust, and any addition to that would constitute a danger, he said. One clause contained in Oakland's contract with Tagami's company allows the city to take actions affecting his development rights, if, after a public hearing, the city determines there is sufficient evidence that the health and safety of residents and workers could be harmed. But Chhabria, called the city's official report on the health and safety impacts of coal dust "pretty vague" and said he needs some kinds of comparison to understand how much more deadly particulate matter would be spewed into the air by allowing coal shipments. That official report was prepared by Environmental Science Associates (ESA). But at today's hearing, one of Tagami's attorneys, Robert Feldman, criticized what he said were errors in the report. He called ESA's work "completely screwed up" and "speculative nonsense." Feldman said ESA massively overestimated coal dust emissions from trains and warehouses by using a mathematical model based on a pile of fine coal dust on a concrete pad instead of an actual pile of coal rocks. "If you go, phew!, to fine dust," said Feldman, blowing into the palm of his hand as if he were spewing dust into the courtroom, "it's going to go everywhere." Feldman said the measurement led to a conclusion that was about 17-times greater than what a better method would have found. Judge Chhabria also criticized the ESA report, saying that numbers regarding particulate emissions in several tables appeared to be inaccurate and didn't add up. Feldman said some of the measurements and methods came straight from the Sierra Club, which he accused of having an explicit goal of stopping all coal mining and exports. "If these numbers aren't true," said Chhabria about information in the ESA report, "they can't be substantial evidence," meaning they couldn't support the city's contention that it abided by its contract with Tagami's company and only banned coal after showing it presented a health threat. But Siegel defended ESA's report, even while he acknowledged it contained at least one typo. He said it was prepared by qualified professionals who used accepted methods. His colleague, Gregory Aker, told the court that Feldman is incorrect about the proper methods used to estimate coal dust emissions from trains and silos. He said the fine dust on a concrete pad was used as a basis for modeling because it more accurately reflects what happens to coal when it's transported on trains. From Utah to Oakland, coal would be exposed to heat and cold, heavy winds, and dust would escape and pile up on train car surfaces. Aker told Chhabria that one of the ESA consultants who did the modeling to estimate dust emissions explained the methods in her deposition and can justify them at trial. "These were not errors," said Aker. "They were very sound numbers." But a year and half ago, when the city first retained ESA to conduct its study, anti-coal activists also pushed for a separate report on the health impacts of shipping coal through Oakland. A volunteer group of public health researchers calling themselves the Public Health Advisory Panel on Coal in Oakland produced a second document that found coal shipments through Oakland "will increase exposures to air pollutants with known adverse health effects including deaths." Chhabria said this study appeared to be more accurate and reliable than the ESA report. Oakland Councilmember Dan Kalb had yet another independent report produced by Zoe Chaffe, an environmental scientists and public health expert, that found that any additional particulate matter emitted by the coal trains and terminal "should be expected to negatively affect the health of workers at the proposed terminal, residents of adjacent communities, and visitors, commuters, and people recreating near the terminal and former Army Base site." The various reports will likely be the subject of intense scrutiny at next week's trial when Chhabria decides whether they provided evidence of a substantial health and safety threat sufficient to justify the city's coal ban. As for arguments that the city's coal ban is preempted by interstate commerce laws, Chhabria didn't seem inclined to agree with Tagami. Tagami's lawyers argued today that cities can't enact laws that stop the shipment of goods bound for interstate commerce, and that's exactly what Oakland did. They also argued that Oakland's coal ban discriminates against out-of-state companies by barring them from bringing their products through California. In this case, Bowie Resource Partners, a Kentucky coal mining corporation, is in contract with Tagami's company to bring millions of tons of coal from its Utah mines to the Oakland marine terminal. (Bowie is also financing Tagami's suit against the city.) "I'm not feeling it," Chhabria said about the discrimination argument. "I agree it stops shipping coal out of Oakland and therefore through the terminal via rail," he explained, "but it would also stop coal mined in the Sierra Nevada, right?" According to Chhabria, because the coal ban would also apply to in-state companies, it doesn't discriminate against Bowie, an out-of-state corporation. And on the matter of whether Oakland is preventing interstate commerce, Chhabria acknowledged the coal ban has an impact on shipments, but he indicated that the city also has a right to exercise its police powers to regulate activities within its geographic jurisdiction, especially if the purpose is to safeguard public health. "I don't think the Commerce Clause is so powerful," Chhabria remarked about the section of Constitution that gives the Congress the power to regulate foreign trade and trade across state lines. He compared Oakland's coal ban to a recently upheld statewide ban on the possession and sale of shark fins. "What it means is: You can't bring them across the border," the judge said. Although the shark fin ban affects international and interstate commerce, Chhabria said it was within California's right to ban them for conservation and public health purposes. However, even though he expressed skepticism, Chhabria declined to rule today on whether the coal ban violated the Commerce Clause, saying instead that he would take it under consideration but that he hoped to resolve the case purely on the question of whether Oakland violated its contract with Tagami's company by banning coal. In three orders issued yesterday, Chhabria threw out several other arguments made by Tagami's attorneys about the coal ban. They had claimed that federal laws regarding the regulation of railroads, hazardous materials transportation, and shipping preempted and therefore nullfied Oakland's coal ban. For next week's trial, Chhabria has ordered each side to present to more than six hours of witness testimony about the contract between Oakland and Tagami's company and whether there was sufficient evidence that the environmental impacts are serious enough to warrant the coal ban. Tagami's attorney, Feldman, said the case was moving at "warp speed." And one key witness, Claudia Cappio, who was the assistant city administrator who oversaw the coal ban ordinance, might have her vacation cut short because her testimony is required. After retiring from the city several weeks ago, she took a trip to Cuba. Chhabria said Cappio should be prepared to testify as early as next Tuesday. SAN FRANCISCO (CN) — A federal judge Wednesday refused to dismiss a challenge to Oakland, California’s ban on coal exports, clearing the way for trial between the city and developers.

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria said neither party had sufficiently explained the evidence, making it difficult to rule on whether the ban violated the city’s contract with developers of a West Oakland shipping terminal fighting to export coal to Asia. He set a bench trial for Jan. 16. “I feel I have not been given enough understanding of the evidence that was in the record that was before the City Council,” Chhabria said in the four-hour hearing. “Was the City Council given the ability to judge whether the amount of emissions from the facility would pose not merely a danger but a substantial danger? That’s what the trial is going to be about.” Developers of the Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal (OBOT), including Phil Tagami, a friend of Governor Jerry Brown, want to haul coal by train from nearly 1,000 miles away in Utah and ship it to Asia through the $250 million facility, which is being built on an old Army base. But in June 2016, the Oakland City Council passed two measures prohibiting the storage and handling of coal and petroleum coke at any bulk materials facility in the city. Multiple studies found that coal dust blowing off trains into nearby neighborhoods could cause asthma or cancer. The new regulations brought the project to a halt. Tagami sued, claiming the regulations on what would have been one of the largest coal-export terminals on the West Coast violate a 2013 development agreement and the Constitution, and are preempted by federal rail and shipping laws. The facility would be capable of exporting up to 10 million tons of coal annually. California today exports less than 3 million tons annually. Oakland says it has the right to enact health and safety regulations, such as the coal ban, when there is “substantial evidence of a substantial danger” to public health. At the June 2016 meeting, city officials cited multiple expert reports on which they based the substantial-danger finding, all of which concluded that storing and handling coal at the terminal would hurt air quality and health in West Oakland. West Oakland is primarily composed of poor people of color. Due to their proximity to major freeways and industry at the Port of Oakland, residents are exposed to heavy pollution and suffer from elevated cancer rates, according to the city and the California Air Resources Board. Oakland does not want to exacerbate neighborhood pollution with coal dust. Attorney General Xavier Becerra reiterated the city’s arguments in an amicus brief. But Tagami attorney Robert Feldman told Chhabria on Wednesday that the coal ban violates the development agreement. Feldman, with Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, called the conclusions by one of the city’s experts, Environmental Science Associates “speculative nonsense” based on math that was “completely screwed up.” Feldman said the environmental planning firm used the wrong standard to estimate the amount of emissions the terminal would create, leading it to conclude it would create 6 tons of emissions a year, 17 times more than it actually would. “The report isn’t worth the paper it was written on,” Feldman said. Oakland’s attorney Kevin Siegel, with Burke, Williams & Sorensen, countered that the 6-ton estimate was “reliable substantial evidence” from an expert. But when Chhabria asked him to justify the number, Siegel said he “cannot point to the underlying data.” “That’s your job at trial,” Chhabria said. “If the numbers are wrong, they can’t be relied upon as substantial evidence.” In his motion for summary judgment, Tagami, whose Oakland-based real estate firm California Capital and Investment Group owns the terminal, said the city knew before signing the development agreement that the terminal might handle coal, then bowed to political pressure against coal. Hundreds of speakers implored the City Council at its June 2016 meeting to pass the ban, after four Utah counties said they planned to invest $53 million in the terminal in exchange for reserving roughly 50 percent of it for their coal. Councilmember-at-large Rebecca Kaplan said in the meeting that California local, state and federal agencies had indicated they would pull funding if the project proceeded with coal included. Two months later, Gov. Brown signed legislation banning state transportation funding for new bulk coal-shipping terminals. But the law left funding intact for existing coal projects, such as Tagami’s. Tagami declined to comment after the Wednesday hearing. Oakland claimed in its summary judgment motion that Tagami “surreptitiously” sought to include coal in the project while denying his intent to do so. The city says Tagami discussed handling coal there with potential business partners as far back as 2011, but dismissed rumors that he intended to do so as “simply untrue.” Meanwhile, he struck a secret deal with Terminal and Logistics Solutions to sublease the Army property for $1.2 million and operate the facility, according to the city. That company is owned by Bowie Resources Partners, a Kentucky-based coal producer that operates mines in Utah and planned to ship its coal by rail to the Oakland terminal for export, according to both motions for summary judgment. Oakland claims that Bowie is funding the lawsuit. “OBOT secretly pursued plans to bring millions of tons of unhealthy, dust-generating, spontaneously combustible substances to the Terminal,” Siegel wrote in the city’s brief to the court. “OBOT communicated with the City about plans for other products at the Terminal, but was silent as to any plans regarding coal.” Chhabria said he would defer ruling on the summary judgment arguments regarding the Constitution’s dormant Commerce Clause, which bars local governments from passing laws restraining interstate commerce. However, he indicated he would rule for Oakland, saying cities can ban the export of a certain product if it endangers their citizens. He declined to hear arguments on the federal preemption claims. Attorney General Becerra’s amicus brief accuses the terminal’s developers of “attempting to expand the reach of federal preemption and the dormant Commerce Clause doctrine to prevent Oakland from exercising its police power to protect some of its most vulnerable residents from dangerous pollution.” West Oakland residents die 12.4 years sooner than residents in richer Oakland neighborhoods, Becerra wrote, and the estimated lifetime potential cancer risk in West Oakland from emissions from the nearby port is about seven times that of the region as a whole. He cited reports by the California Air Resources Board and the Alameda County Public Health Department. “Breathing clean air should not be a privilege for the few, but a right for all,” Becerra tweeted on Monday. “Unfortunately, in Oakland, people of color would have to bear the brunt of the pollution emitted by the handling of coal and petroleum coke at the Bulk Oversized Terminal.” https://www.courthousenews.com/oaklands-ban-on-coal-exports-headed-for-federal-trial/  801-257-8713 801-257-8713 Initial arguments start Wednesday in a federal lawsuit backed by Bowie Resource Partners to reverse Oakland’s coal ban — and potentially open new markets for Utah mines.  (AP file photo) The former Oakland Army Base pier at left and the Port of Oakland at lower right in Oakland, Calif, seen in 2016. The city's ban on coal handling at the former base, which is being re-purposed into a massive distribution center and export terminal, has sparked a lawsuit that goes to trial Jan. 16 — with heavy financial backing from one of Utah’s leading coal producers. Between Utah’s rich coal beds and potential markets overseas lie 850 miles of rail track and 5,000 miles of ocean that converge in the California port city of Oakland. A proposed Oakland export terminal once promised an economic lift for distressed portions of California’s prosperous East Bay — and a new conduit for Utah’s coal to reach Asian markets. But the controversial project is now mired in a legal swamp, as one of Northern California’s most prominent developers takes on his own city over a coal-handling ban Oakland leaders enacted in 2016. Under agreements with the city, which owns the 35-acre site known as West Gateway, Phil Tagami is developing a deep-water bulk-freight loading station on a decommissioned military base at the foot of the Bay Bridge. But those plans jackknifed in 2016 after word got out that four coal-producing Utah counties had pledged $53 million toward the project, called Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, or OBOT, in exchange for guaranteed export capacity.  News of that Utah connection ignited a political firestorm that led to Oakland City Council’s vote to prohibit coal; Tagami responded with a federal suit that heads to trial this month in a San Francisco courtroom. The suit alleges Tagami’s firm holds a “vested right” to process any legal commodity it chooses at the terminal. Key adversaries in the drama include Utah’s leading coal producer Bowie Resource Partners and activist groups looking to reduce global reliance on the carbon-heavy fuel most closely linked to climate change. And according to court filings, the firm that would operate the Oakland export station is a wholly owned subsidiary of Bowie Resource Partners, which is bankrolling Tagami’s suit to the tune of at least $1.7 million. New markets vs. health worries Domestic demand for coal is plummeting as power utilities turn to cleaner energy sources for electricity generation, so industry officials see Asia’s expanding economies as an alternate destination for the West’s relatively clean, high-energy coal. West Coast cities — populated with residents concerned about coal’s greenhouse gas emissions — are balking at the prospect of their ports expanding the trade. But Oakland’s legal rationale for blocking coal is strictly about local impacts to public health as opposed to broader climate concerns, according to Aaron Reavin, an Oakland schoolteacher. “It was totally within [Oakland’s] authority under the agreement with Phil Tagami to act on health and safety issues. There was a tremendous amount of medical and scientific evidence marshaled to support banning the handling of coal,” said Reavin, a coordinator with the grassroots group No Coal in Oakland. “Of course climate issues play into this. To us, they are twin evils.” Reavin’s is among a host of groups — including the California Attorney General’s Office — filing briefs in the lawsuit in support of the coal ban. The Sierra Club, an environmental group, has intervened on Oakland’s side, along with San Francisco Baykeeper, which advocates for ecosystems and communities relying on the bay. On Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria will wade through a series of court motions seeking quick resolution to the case. Both sides are asking the federal judge for summary judgments in their favor without a two-week trial, which is now scheduled to begin Jan. 16. Oakland and its allies say by enacting the coal ban, the city exercised its duty to protect residents from coal dust that would waft off trains, conveyors and loading pits and potentially accumulate to explosive levels in the terminal’s containment structures. The ‘hidden‘ Utah link They also allege Tagami and his associates deceived city officials by falsely denying coal would be part of the project, then concealing the central role they hoped Utah coal would play for more than a year. In 2014, Tagami entered a secret deal with the Bowie subsidiary Terminal Logistics Solutions, granting the coal producer an option to sublease the West Gateway, the city claims in its filings. Under that arrangement, which has netted Tagami $1.2 million in a series of payments from Bowie, the coal producer would own and operate the terminal for the sake of exporting coal from Utah’s Sufco, Skyline and Dugout mines.

In April 2015, a state panel called the Utah Permanent Community Impact Board (CIB) let the cat out of the bag when it approved an unusual $53 million loan to Sevier, Carbon, Emery and Sanpete counties to invest in the project. The investment guaranteed 5 million to 10 million tons of Utah coal would move through the California terminal every year. The revelation stunned Oakland city leaders, who opened a formal inquiry into the environmental and health impacts of processing coal. The city’s subsequent ban on coal handling, however, runs afoul of the law on three grounds, according to Tagami’s suit. It poses an unconstitutional restraint on interstate commerce; it is trumped by three federal laws regulating rail transportation; and it breaches various agreements between Oakland and Tagami’s development firm. The terminal would be designed to keep coal dust from escaping into the environment, Tagami’s lawyers argued in court filings, while existing laws and a permitting process for the project would protect the health and safety of nearby residents and workers. “While the Terminal has always been planned as a multi-commodity bulk terminal,” Tagami’s lawyers wrote, “such terminals often require an ‘anchor tenant’ to make the terminal financially feasible; Bowie’s bituminous coal from Utah is currently the ‘anchor tenant.’ ” |

Gene HazzardDon't Be Envious of Evil Men Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||

- Home

- Sanjiv Handa

- Gene's Blog

- Rotunda RFP

- Gene Hazzard -Keeping eyes open

- Chronology of Tagami's scheme of Private-Public Partnership with City Projects

- Another Tagami scheme - Rotunda Building deal

- Oakland Army Base

- Billboards in Oakland

- Port of Oakland

- Oakland Raiders?

-

Who is running Oakland?

- Jerry Brown

- Don Perata

- Judge Robert B. Freedman

- Jacques Barzaghi

- Gawfco Enterprises

- Deception

- Doug Bloch

-

Phil Tagami

>

- SF Business Times November 20, 2005

- Rotunda wrestling

- A conversation with Oakland developer Phil Tagami

- Audit of $91 million Fox Theater project

- Tagami Conflict

- CCIG Response to Oakland Works

- Oakland developer Phil Tagami named to state medical board

- ‘Shotgun Phil’ hits another bullseye — with governor’s help

- CleanOakland Store

- CenterPoint Properties

RSS Feed

RSS Feed